The Burden of Falling Education Standards by Shalini Reddy

Today, there are more schools, teachers, education leaders, and companies creating learning materials than ever before. Professional development programmes, curriculums, and online resources are everywhere. On the surface, this should be education’s golden era. Yet across the world, we continue to hear that learning outcomes are in fact falling. This contradiction has puzzled me throughout my years in education and leadership. Why is it that despite so much investment and effort, so many systems still struggle to give learners the education they deserve?

The globally recognised organisation for measuring educational standards in OECD countries, PISA, echo these concerns as they report “mean performance fell by ten score points in reading and by almost 15 score points in mathematics, which is equivalent to three-quarters of a year’s worth of learning.” This is the steepest decline in PISA’s 20-year history. Importantly, the OECD organisation makes it clear that “the decline in performance can only partially be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, with falling scores in reading, science and maths already apparent prior to 2018.” In other words, the pandemic exposed cracks in the system, but it did not create them.

I gained insight into the heart of this conundrum by talking to the school leaders and educators from around the world, as I attended conferences. They shared their struggles openly. Some challenges are tied to politics, economics, or culture, but I also noticed common threads that cut across borders.

One recurring theme was the problem with how teachers are perceived. When a student performs poorly, a teacher shoulders the complete responsibility, as people assume they are just bad at teaching. However, a closer glance reveals that most teachers work tirelessly in systems that don’t often provide them with the guidance, resources or trust they need to thrive. A RAND survey even found that teachers work an average of 53 hours per week – seven hours more than other working adults – much of which is often unpaid.

Another piece to this problem is a misalignment in school leadership. School leaders are too often over-burdened with paperwork and administrative tasks, leaving little time for what matters most – guiding teaching and learning. As Meyer and MacMillan note, principals have increasingly become “agents of accountability” rather than instructional leaders. Teachers flourish when they are coached, mentored, and supported, yet too often, school leaders are constrained by systems that demand compliance over collaboration.

Parents add another layer of complexity to this conundrum. Their expectations and concerns are important, but those expectations also constantly evolve. Schools often struggle to balance these individual demands with a collective vision that serves all learners. They must remain responsive to parental perspectives while exercising professional judgment, striving to advance the best interests of all students without diminishing the valuable partnership between schools and families. It is a challenging task – but one that lies at the heart of education’s shared responsibility.

Another possible contributor to this problem, may be frequent changes to school leadership. Each new principal brings fresh ideas and priorities, but when leadership turns over too often, school values, culture, and policies can shift before they take root. This continual change unsettles both teachers and learners, who thrive in environments marked by consistency and trust. Over time, such instability can erode morale, disrupt long-term goals, and make it difficult to sustain meaningful improvement across the school community.

Government policies also play a decisive role in shaping schools. Reforms are often introduced with good intentions, aiming to raise standards or address pressing challenges. Yet when such changes are implemented without sufficient clarity, consultation, or preparation, they can disrupt more than they help. Frequent policy shifts leave educators struggling to adapt, diverting time and energy away from teaching and learning. For reforms to truly succeed, they must be grounded in evidence, supported by training and resources, and developed in partnership with those who work closest to students.

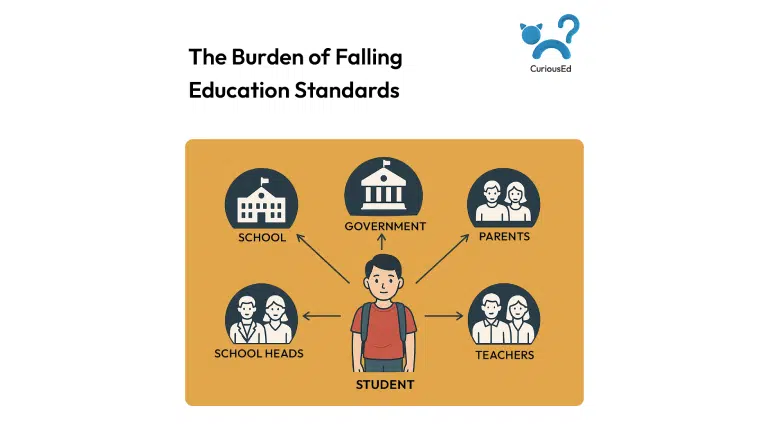

Amid all this, a troubling pattern emerges – it becomes easy to assign blame. School heads highlight government policies. Boards and owners talk about finances and pressures. Each perspective holds some truth, yet as this cycle of blame continues, attention drifts from what truly matters – the children at the center of it all.

Children in our schools, who have no decision-making power, are the ones who feel the most impact. When teachers are unsupported, when leadership is unstable, or when systems put processes above people, learners carry the weight. The very group education that is meant to serve ends up suffering the most.

I don’t believe there is a simple solution. Education is complex and shaped by many forces beyond the classroom. But I do believe there is a way forward. It begins with each of us – leaders, teachers, parents, boards, and policymakers.

Leaders can focus more on guiding instruction than on paperwork. Teachers can be trusted and encouraged to innovate. Parents can work with schools as partners rather than as clients. Boards can nurture stability and culture instead of constant change. Governments can support schools rather than dictate to them.

If each of us takes even small steps in this direction, together we can strengthen our schools.

This reflection is not written to criticise, but to spark dialogue. Every stakeholder has a role to play, and each of us has, at times, fallen short. These are simply my reflections from years of working with schools, and I share them in the hope they resonate with others who care deeply about education.

And that, after all, is the purpose of education.

This belief has guided my journey, and it continues to shape the work I do today.

By Shalini Reddy – Co-founder of CuriousEd and Manthan International School

References:

Miller, D. (2024, June 18). Teachers report worse pay and well-being compared to similar working population. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/news/press/2024/06/18.html

Meyer, M. J., & MacMillan, R. B. (2001). Instructional leadership ain’t what it used to be. International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning, 5(13). https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/iejll/index.php/iejll/article/download/505/167/505